Jacob Knapek: the Plant Guy

by Garret Fettig, ’23

As a high school student in St. Cloud, Minn., Jacob Knapek had no idea he’d spend his future days thinking about grass.

Not just any grass — specifically, native prairie grasses. Though Minnesota is the Midwest’s most forested state, there’s more to their terrain than trees. Prairie once covered one-third of Minnesota’s 86,000 square miles. Today, less than 1% of that landscape remains.

When Knapek learned this during a high school Minnesota Ecology class, it changed the course of his future. A seed of interest in natural science sprouted in him that eventually lead to Valley City State University.

“That fact opened my eyes and made me think of how much we’ve changed the natural world,” Knapek said. “I became passionate about native plants, and I learned about ecological restoration, which is the process of using native plants to restore the environment to what it once was.”

Knapek will graduate from VCSU this December with a degree in Fisheries and Wildlife Science. Knapek’s passion for native and prairie plant life has only grown stronger as he’s seized opportunities at VCSU and beyond.

In his academic department at the Rhoades Science Center on campus, others unofficially refer to Jacob as “the plant guy.” He welcomes the title.

“Everyone has to nerd out about something,” Knapek said with a laugh. “For me, it’s plants. I’m fascinated by how they operate, their ecosystems, their niches. There are just little things about different species that are really cool.”

He spent his childhood in nature’s playground, enjoying the outdoors and learning how to hunt, growing twin interests in nature and science. Eventually, these blended into one.

When it came time to search for colleges, Knapek received a letter in the mail about the VCSU Fisheries and Wildlife program. That seed of interest inside him sprouted, and Knapek decided to visit campus. After a positive, personalized visit with professors, he was committed to attending.

Sustainable Landscaping

Knapek started his college journey in the fall of 2019, and knew how important gaining seasonal work and field experience were for his future. Possessing hands-on abilities and technical skills separated students from the crowd. Knapek found ways to gain both.

In the fall of 2020, Valley City was adding two more pollinator gardens to the orchard on 5th Avenue Northeast. Dr. Casey Williams, a professor in the Fisheries and Wildlife Department, had noticed Knapek’s interest in plants and sustainable landscaping. Williams mentioned the gardens project to him, and Knapek eagerly agreed to take it on.

“I got to choose the species to plant, design the layout, and make all of the purchasing decisions,” Knapek said. The gardens have thrived. Knapek said kiosks will soon display information he’s gathered, to educate orchard visitors about sustainable landscaping with native plants.

This project was the beginning of Knapek’s efforts in sustainable landscaping and restoration. During 2020 and 2021, he worked as a greenhouse technician for Minnesota Native Landscapes (MNL), an ecological restoration company. They restore and manage clients’ land, providing seeds and resources — a one-stop shop of restoration. MNL serves a wide variety of clients, creating small gardens for homeowners and selling seed for large-scale projects.

Research Experience

In the spring of 2022, Knapek decided to continue studying and working with plants at a graduate level. He soon discovered that his time leading the pollinator gardens project and working at MNL was well-spent.

Knapek reached out to schools about their graduate programs. Dr. Kathryn Yurkonis, a professor of Biology at the University of North Dakota, answered his call and specifically expressed interest in Knapek’s previous work.

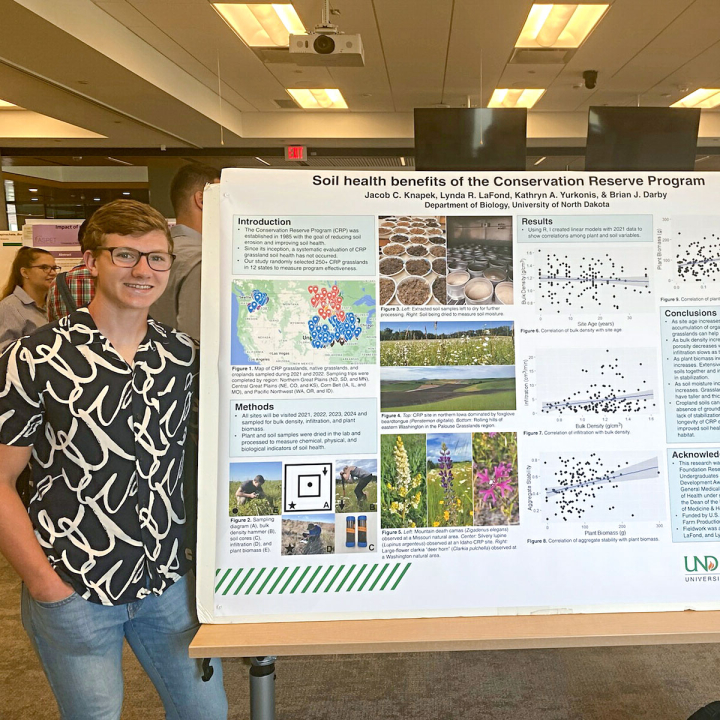

Yurkonis and UND had been enlisted to help study the benefits of the federally funded Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), a national undertaking. The program allows farmers to take land out of agricultural production for a certain amount of time in return for compensation. Their land is planted to replicate native prairie. This has many environmental benefits and enriches the soil.

“If you can restore the soil a little bit, then farming is going to be better,” Knapek said.

The project specifically measures soil health benefits of the CRP on a large scale. It’s a systematic evaluation of the program’s effectiveness, across 12 states over four years. Every summer, plant and soil samples are collected.

Knapek earned his place on Yurkonis’ team for the summer of 2022 through UND’s Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) program.

“[Yurkonis] liked my experience,” Knapek said. “That was one of the reasons she wanted me on the project. MNL supplies seeds for CRP plantings, so I was able to work on this project that my previous work had supported.”

In their second summer of soil sampling, UND’s team visited over 250 CRP sites. The team went as far south as Missouri and Nebraska and as far west as Oregon and Washington. Knapek went to Iowa, Missouri and Illinois on his first major trip. Washington, Oregon and Idaho were stops on his second.

One of the fields at Minnesota Native Landscapes.

One of the fields at Minnesota Native Landscapes.

“I would say the trip out west to Washington was probably my favorite, just because it’s so different from what we see here. There are so many cool plants that I didn’t know existed,” Knapek marveled. Finding new plants in their natural habitats? Things don’t get much better than that for the plant guy.

The REU program concluded in August. Participating students created posters about their work done that summer. Knapek enjoyed the chance to share what he’d done and learned during the busy summer months.

Upon his return to Valley City, Knapek applied to UND’s graduate school. The timing of his summer experience, which gave him a head start on graduate work, influenced his final choice. At UND, he’ll focus on the same project he began this summer. The project will end in 2024 in the same year he’ll graduate with his master’s degree.

Restoration’s Importance

In his application to UND, Knapek reflected on how his understanding of ecological restoration has changed throughout college. He wrote:

“It is easy to envision a pristine species-rich grassland after seeding a bare field, like a painter hopes for a masterpiece while looking at a blank canvas, but that vision is likely unattainable. This latest experience taught me that there is no ‘perfect restoration’ as I originally perceived, because there will always be an ongoing battle with invasive species and other environmental factors.”

For Knapek, it’s absolutely a battle worth fighting. When humans cause harm for the sake of agriculture or development, it harms the entire ecosystem. The consequences of such destruction are far-reaching.

“Grasslands provide services like reducing soil erosion and improving the soil health. They provide a lot of wildlife habitat. They increase biodiversity. They help to purify water. They decrease flooding,” Knapek explains. “Prairies can really hold a lot of water, and if you think of North Dakota in the spring, a lot of places flood because there is no ground cover. If plants were there, that would be reduced.”

The environmental benefits of prairie land abound, but Knapek adds that some might be surprised by the different areas native plant restoration can help with — like the economy.

“We’re not really going to care about the environment, to be honest, if there’s no economic benefit to it,” Knapek said. “But when you have well-functioning ecosystems with high numbers of native plants, it does save money.”

In a world plagued by constant worry over climate change and its impact, Knapek finds economic and agricultural solutions in the restoration of native prairie.

“When you think of flood damage and damage by water in general, in this part of the U.S., that can be a lot of money lost,” Knapek said. “If you have areas with a good grassland ground cover, that can help save money as well as improve the soil. If your soil is poor, you’re not going to produce as many crops, and that’s going to take money away from you.”

After earning his master’s degree in Biology, Knapek aims to be in a position where he can further his fascination with flora. He’s considered becoming a botanist or a plant ecologist, either for a government agency or private company.

Ultimately, Knapek hopes to do his part for the prairie — and all of plantkind.

“I just want to be able to make important, sustainable decisions in conservation, and manage our ecosystems and their plant aspects to make sure they survive for the future.”